Science is uncovering more novel ways to transform those smelly, spent banana peels decaying in your garbage into something people might actually want to eat. Around a third of the world’s overall food supply is wasted or lost every year. That, according to the UN’s World Food Program, adds up to around $1 trillion worth of lost food every year. All of this waste may send as much as three billion new tons of greenhouse gasses emitted into the atmosphere. But new research into Neurospora intermedia, a fungus at the heart of a classic fermented Indonesian dish, may offer a partial solution to this growing agricultural dilemma.

The study, published last week in Nature Microbiology reveals Neurospora may possess a unique ability to remove indigestible plant material found in common food waste and turn that detritus into edible and surprisingly tasty new dishes. Now, multiple Michelin star chefs are using those findings to reimagine normally discarded food scraps as totally new fine-dining dishes. The ultimate goal: use the fungus’ transformative properties to simultaneously reduce food waste and create tasty treats.

“Our food system is very inefficient. A third or so of all food that’s produced in the U.S. alone is wasted, and it isn’t just eggshells in your trash,” former chef and research lead author Vayu Hill-Maini said in a statement. “It’s on an industrial scale. What happens to all the grain that was involved in the brewing process, all the oats that didn’t make it into the oat milk, the soybeans that didn’t make it into the soy milk? It’s thrown out.”

A fungus with transformative properties

Hill-Maini began his research with an exploration of the Indonesian dish oncom, a fermented product traditionally derived from discarded soy leftovers from making tofu. Hill-Maini performed a metagenomic survey of oncom samples to determine what exactly was responsible for turning the soy waste into an edible product. The results revealed Neurospora, in the form of a mold, was dominant. A closer look into the underlying genetic structure of the fungus revealed something even more interesting; multiple enzymes capable of breaking down indigestible plant material like pectin and glucose and transforming it into material digestible by humans. The entire transformational process occurs in just around 36 hours.

Further analyses showed this process works not just for soy byproducts, but around 30 other types of food waste products from almond shells and banana peels, to stale rice bread. In each case, the fermentation process rapidly reimagined these waste products into seemingly new food with unique, often unexpected flavor profiles. Even more surprising, analyses of the Neurospora from the oncom dish sample and Neurospora found in the wild found striking fundamental differences. Indonesian cooks, the study suggests, may have unintentionally created a distinct, domesticated strain of the fungus.

“The fungus readily eats those things and in doing so makes this food and also more of itself, which increases the protein content,” Hill-Maini said. “So you actually have a transformation in the nutritional value. You see a change in the flavor profile. Some of the off-flavors that are associated with soybeans disappear.”

Michelin star chefs use Neurospora to create entirely new dishes

Armed with that chemical knowledge, Hill-Maini decided to partner with prominent chefs in the US and Europe to explore whether or not the fungus could be adapted for a more westernized palate. To start, Hill-Maini partnered with Rasmus Munk, head chef co-owner of the Copenhagen-based two Michelin star restaurant “Alchemist” to conduct a baseline taste test. They presented the traditional red oncom dish to 60 testers who had never tasted it before. They consistently rated it a six out of nine in terms of tastiness. Overall, the tasters said the oncom had an earthy, nutty, and, maybe not unsurprisingly, mushroomy taste to it. At the same time, it was still relatively subtle.

“Its flavor is not polarizing and intense like blue cheese,” Hill-Maine said. “It’s a milder, savory kind of umami earthiness. Different substrates impart their own flavors, however, including fruity notes when grown on rice hulls or apple pomace.”

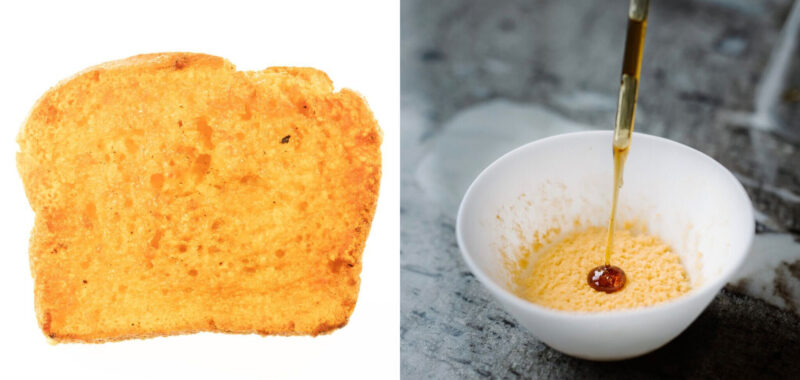

Munk and Andrew Luzmore, chef in charge of special projects at a New York-based Michelin star restaurant called Blue Hill, set out to create entirely new dishes based around Neurospora’s transformative properties. At Blue Hill, Luzmore experimented by placing the fungus mold on top of several days old bread. Once the 36 hour fermentation process was complete, Luzmore took the concoction and fried it up. The result was something that looked and tasted remarkably like a toasted cheese sandwich even though no cheese or dairy at all was involved.

“It’s incredibly delicious,” Luzmore said in a statement. “It looks and tastes like you grated cheddar onto bread and toasted it. It’s a very clear window into what can be done with this.”

Munk, by contrast, opted to create a fungus-inspired dessert. For his dish, the chef incorporated the fungus sample into a colorless and bland rice custard. After a 60 hour fermentation process, the once bland custard came out sweet with a surprisingly pineapple-ey, fruity flavor profile. Munk is adding the oddball sweet to his restaurant’s menu, served alongside a jelled plum wine and lime syrup.

“We experienced that the process changed the aromas and flavors in quite a dramatic way—adding sweet, fruity aromas,” Munk said in a statement. “I found it mind-blowing to suddenly discover flavors like banana and pickled fruit without adding anything besides the fungi itself.”

Hill-Maini, the researcher, says these culinary experiments were important in order to ensure the study findings “don’t just stay in the lab.” That said, his ambitions are much larger than the limited, rarefied confines of the fine-dining elite. In theory, Hill-Maini believes this natural occurring fermentation process could be applied to on an industrial scale to simultaneously reduce common food waste and introduce new, nutritionally rich protein substitutes into the marketplace. The fact that they seem to taste decent is an added bonus. More fundamentally, Hill-Maini says–quite ambitiously–that these revelations, rooted in centuries of traditional Indonesian cooking, could help reimagine what we actually consider “waste” in terms of food.

“My long term vision is to look at these large waste things that come out of the food system and look at them as an opportunity, as an ingredient in and of itself,” Hill Maini said. “Why does it have to be called waste?”