Some teenage Japanese eels have found a way to avoid becoming a fish’s next meal. Anguilla japonica eels can escape a predator’s stomach through the fish’s gills. Now, scientists are using X-ray videography to watch just how eels accomplish this. The findings are detailed in a study published September 9 in the journal Current Biology.

“They escape from the predator’s stomach by moving back up the digestive tract towards the gills after being captured by the predatory fish,” Yuuki Kawabata, a study co-author and ecologist at Nagasaki University in Japan, said in a statement. “This study is the first to observe the behavioral patterns and escape processes of prey within the digestive tract of predators.”

[Related: These snakes play dead, bleed, and poop to avoid being eaten.]

Previously, this team researchers found that some Japanese eels can escape from a predator’s gills after they are captured, but they were not sure how they did it.

“We had no understanding of their escape routes and behavioral patterns during the escape because it occurred inside the predator’s body,” study co-author and ecologist Yuha Hasegawa said in a statement.

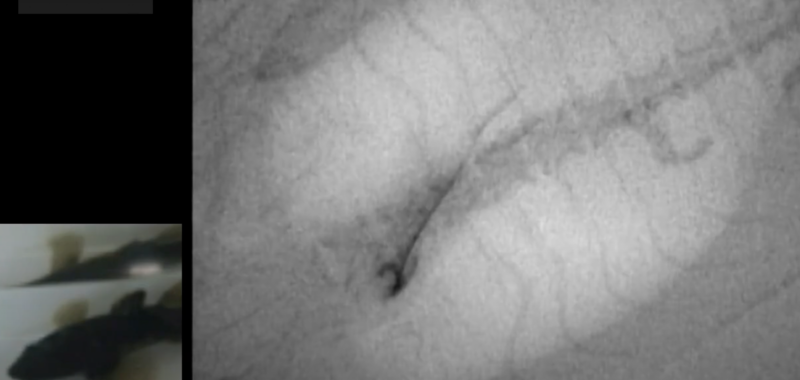

In this new study, the team used an X-ray videography device to see inside of the predatory fish Odontobutis obscura–aka the dark sleeper. In order to see the juvenile Anguilla japonica eels after they had been eaten, the researchers injected the eels with a contrast agent that enhanced their visibility while inside the fish’s digestive tract. Even with the high tech video and dye, it still took the team a full year to get enough convincing video evidence of the escape process. The eels back up, insert the tips of their tails through the fish’s esophagus, inch out part of the way, and then pull their heads free.

Researchers found that all 32 of the eels had at least part of their bodies swallowed into the stomach of their fish predators. After they were swallowed, all but four of the eels tried to get out by going back through the fish’s digestive tract toward its esophagus and gills. Of those, 13 managed to get their tails out the fish gill. Nine successfully escaped through the gills. It took the escaping eels about 56 seconds on average to free themselves from the predator’s gills.

[Related: How citizen scientists are protecting ‘glass eels.’]

“The most surprising moment in this study was when we observed the first footage of eels escaping by going back up the digestive tract toward the gill of the predatory fish,” Kawabata said. “At the beginning of the experiment, we speculated that eels would escape directly from the predator’s mouth to the gill. However, contrary to our expectations, witnessing the eels’ desperate escape from the predator’s stomach to the gills was truly astonishing for us.”

A closer look revealed that despite the similarities, the eels didn’t always rely on the same route through the gill cleft to escape. Some of them also circled along the fish’s stomach, seemingly in search of another way out.

According to the team, this study is the first to show that the eel Anguilla japonica can use a specific behavior to get out of the stomach and gills of its main predator after being eaten and the first to capture it on video. The X-ray methods used in the study could also be applied to observations of other internal predator-prey behaviors. Researchers also hope to learn more about what characteristics of this process make for a successful escape by the eels.