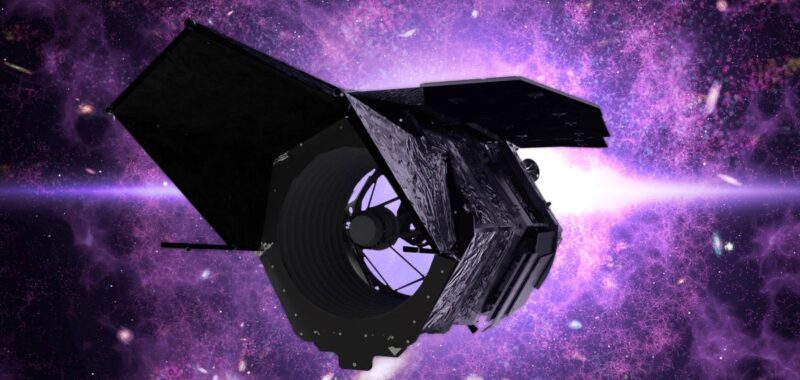

Technicians at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center are nearing the finish line on the space agency’s newest flagship astrophysics mission. Called the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, the eagerly awaited $3.5-billion observatory could solve the secrets of the dark universe, spot untold undiscovered worlds and light the way toward finding alien life. It only awaits final integration and testing, a short hop down to Cape Canaveral, Fla., and a longer journey to a sun-circling orbit near the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). In a triumph for NASA, reliable sources say that Roman could launch as early as the fall of 2026, well ahead of its May 2027 target and potentially under budget.

But a leaked draft of the president’s 2026 budget request, which Scientific American has reviewed, instead calls for canceling Roman.

“This is nuts. You’ve built it, and you’re not going to do the final step to finish it?” says astrophysicist David Spergel, president of the Simons Foundation and former co-chair of Roman’s science team. “That is such a waste of taxpayers’ money.”

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Roman isn’t the only casualty in the president’s draft NASA budget, which is still in flux and will ultimately require congressional approval. The proposal cuts heavily into the $25-billion space agency’s science division, home to missions that include JWST, the twin Voyager probes, the Hubble Space Telescope and a fleet of Mars rovers that have colored in our understanding of the cosmos and captured imaginations worldwide for half a century.

The draft budget includes an almost 50 percent cut to heliophysics, which studies the sun and space weather, reducing it to $455 million; a more than 50 percent reduction in Earth science funding, which includes climate monitoring, taking it down to roughly $1 billion; and a 30 percent cut to planetary science and solar system exploration, resulting in $1.9 billion. The last cut kills the upcoming DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) mission to Venus and NASA’s beleaguered mission to bring rocks back from Mars. Notably, the document also cleaves off two thirds of the funding for NASA’s astrophysics division, which studies stars, galaxies and cosmology, dropping it to $487 million and specifying that “no funding is provided” for telescopes other than JWST and Hubble.

Space policy observers expressed dismay at the budget cuts, particularly at the notion of throwing away a flagship space telescope. “This is a wholly unserious budget proposal,” said Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland, the ranking member of the spending committee for NASA, in a recent statement.

Privately, space policy experts have been even less charitable about the proposal: “It sets back a program that is clearly the leading program in the world—in a historic fashion,” says a former government official, speaking to Scientific American on condition of anonymity because of concerns about retaliation. “You take that program and shoot it through the head.”

NASA has refrained from saying much publicly. A spokesperson for the agency has only issued a statement that it has the draft “and has begun the deliberative process.” (The White House has not responded to requests for comment.) The agency received the draft on April 10, one day after Jared Isaacman, President Donald Trump’s nominee for NASA administrator, insisted in his nomination hearing that the U.S. could send humans to the moon and Mars and “do all the other things” with NASA’s current budget. “I do believe the president is looking to usher in the golden age of science and discovery,” Isaacman said. Now observers suggest that instead of ushering in that golden age, the Trump administration simply seems to be trading in the entire universe.

“If you want to take the most successful fleet of missions ever built, and the leadership that accompanies that fleet, and throw that all away, this is the budget to do it,” says another senior space scientist, speaking anonymously because of concerns about budgetary retribution from the Trump administration. “This budget is like, ‘Here is a shit sandwich with no side of pickle.’ You don’t even get the plate!”

“It’s like 200 Hubbles”

This isn’t the first time Trump’s White House has tried to zero out Roman—it’s the fourth. But in each previous instance Congress kept the program alive. Observers are hopeful that lawmakers will again rescue the telescope because space science has traditionally enjoyed bipartisan support.

In 2020 NASA named the project, which until then had been called the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), after Nancy Grace Roman, an astronomer who played a pivotal role in developing Hubble. The Roman telescope has been ranked as a top priority in astrophysics since a National Academy of Sciences review in 2010—a status that was only bolstered two years later, when the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which builds and operates spy satellites, donated two large, unused mirrors and associated optics to the mission.

American astronomer Nancy Grace Roman at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland in the early 1970s.

NASA/Interim Archives/Getty Images

Designed to survey our own planet, the NRO’s 2.4-meter-wide mirrors match Hubble’s in size. But they have a shorter focal length that makes them better suited for doing wide-field imaging surveys that monitor millions of stars and take broad looks at exploding stars, early galaxies and large-scale cosmological structures. “Every Hubble image you see—make it 100 times bigger,” Spergel says. “It’s like 200 Hubbles. We will survey the entire sky, with Hubble-quality images.”

The project was initially overbudget, but after a hefty course correction, the team is on track to deliver Roman ahead of its planned 2027 launch—and, if so, below cost. That comes on the heels of repeated criticism from federal and congressional watchdogs over price tags and schedule overruns for large space agency missions in the past two decades.

“The team should be given an award, not beat up!” says the former government official. “This is what we want. This is exactly what we want to achieve.”

Riddles in the Dark

Like JWST, Roman sees the universe in infrared light—which means that it can spot very old, very faraway objects whose light has stretched into longer, redder infrared wavelengths as it has traversed the expanse. One of the mission’s primary scientific goals is to gather the multitude of observations we need to understand dark energy, the mysterious force that is causing the universe to balloon outward.

“Roman has the sensitivity we need to understand what’s going on with the 70 percent of the universe that we don’t understand, which is dark energy,” Spergel says.

Crucially, recent results from other surveys suggest that this still mysterious dark energy, whose force is seemingly pushing galaxies apart at an accelerating rate, might surprisingly weaken over time. And Roman is designed to be complementary to the European Space Agency’s Euclid telescope, which makes similar observations at visible wavelengths, and the U.S.’s powerful, ground-based Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is coming online later this year in Chile. “These are not missions that do the same thing,” says Henk Hoekstra, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who studies dark energy. “We have this strange universe—would you trust a single result and build our whole understanding of the universe on just this one measurement?” Another Roman instrument—a starlight-blocking coronagraph—is a key prototype for NASA’s next major astrophysics flagship mission, the Habitable Worlds Observatory. That space telescope will look for signs of life in the atmospheres of faraway, habitable planets. Zeroing out Roman would mean losing all the information we’d get from that tech demo. And observers say the cut would also erode current and future astrophysics. Plus, pulling the plug on Roman would not only erode expertise; it would also damage international collaborations. For those to work, Hoekstra says, international partners need to trust that “people can’t just suddenly turn off the tap and say, ‘We’re not going to do this.’”

Many of the budget’s proposed cancellations do exactly that.

“Why do we even plan on doing great things if, on a whim, we can just decide ‘nah’?” the senior space scientist says. “These things take a generation to build and enable multiple generations of scientists. They should not be blithely thrown away.”