The International Space Station, or ISS—our largest home away from home—has been continuously occupied since November 2, 2000. That month Popular Science published an interview conducted by Science Editor, Dawn Stover, with two of the ISS’s three seminal residents, NASA astronaut William Shepherd and Russian cosmonaut Sergie Krikelev. The third was another Russian cosmonaut, Yuri Gidzenko.

Krikalev told Stover that he considered himself lucky to be one of the ISS’s first residents. “This is the first example of how we’re going to build things in space,” he noted. Shepherd was more pragmatic. He hoped the ISS’s treadmill “and other exercise equipment” would help the crew minimize muscle and bone loss—a negative side effect of zero gravity—during their four-month stay.

A product of fifteen different countries and their associated space agencies—including the US’s NASA, Russia’s Roscosmos, the European Space Agency, the Japanese Exploration Space Agency, and the Canadian Space Agency—the ISS functions as a home, a laboratory (so far conducting more than 3,700 experiments), and, lately, a Spacebnb for ultrarich private citizens seeking a short getaway. According to NASA, 280 individuals from 23 countries have visited the ISS, including trained astronauts and cosmonauts. Of those, 13 were private citizens, which NASA refers to as “spaceflight participants.”

It takes as little as four hours to commute to the ISS from a launchpad on Earth. The key is to book one of the eight docking ports in advance to avoid long wait times. Walk-ups—or fly-ups—are generally not welcome, although a June 2024 snafu on Boeing’s Starliner forced its two-person crew, NASA astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams, to extend their stay—by months.

When Stover asked if Krikalev expected any glitches, he responded emphatically, “I would expect not a couple, but a couple dozen!” One of the worst culprits were the Windows NT laptop computers the astronauts used for some communications, email, and as a graphical user interface to the more important command and control modules (which, fortunately, could be operated independently). During their initial stay, Shepherd complained about the time they had to spend troubleshooting laptop errors.

In a March 2001 Popular Science feature, “Living on Alpha,” writer Jim Schefter chronicled the early days of ISS life for the four astronauts. “A little grumpiness may be unavoidable,” he wrote. “The new residents are 230 miles up and stuck for a four-month stay. They can’t step into the backyard to cool down. Life aboard the newly christened space station Alpha is characterized by free-floating objects and people whizzing around very tight quarters.” The initial living area included only three rooms. Later modules, such as the Destiny laboratory module and Harmony module, enabled roomier accommodations.

But no home lasts forever. After circling our planet for more than three decades, the ISS is scheduled to be deorbited—which means a controlled crash in an ocean, away from populated areas—in 2031. By then, NASA hopes to lease space (the habitable variety) on privately owned and maintained space stations, like Blue Origin’s Orbital Reef. Such space stations will be designed to accommodate space tourism as well as public and private research. Shepherd noted in his 2000 interview with Stover, “The crews after us will have a lot more room, so their living conditions will be better.”

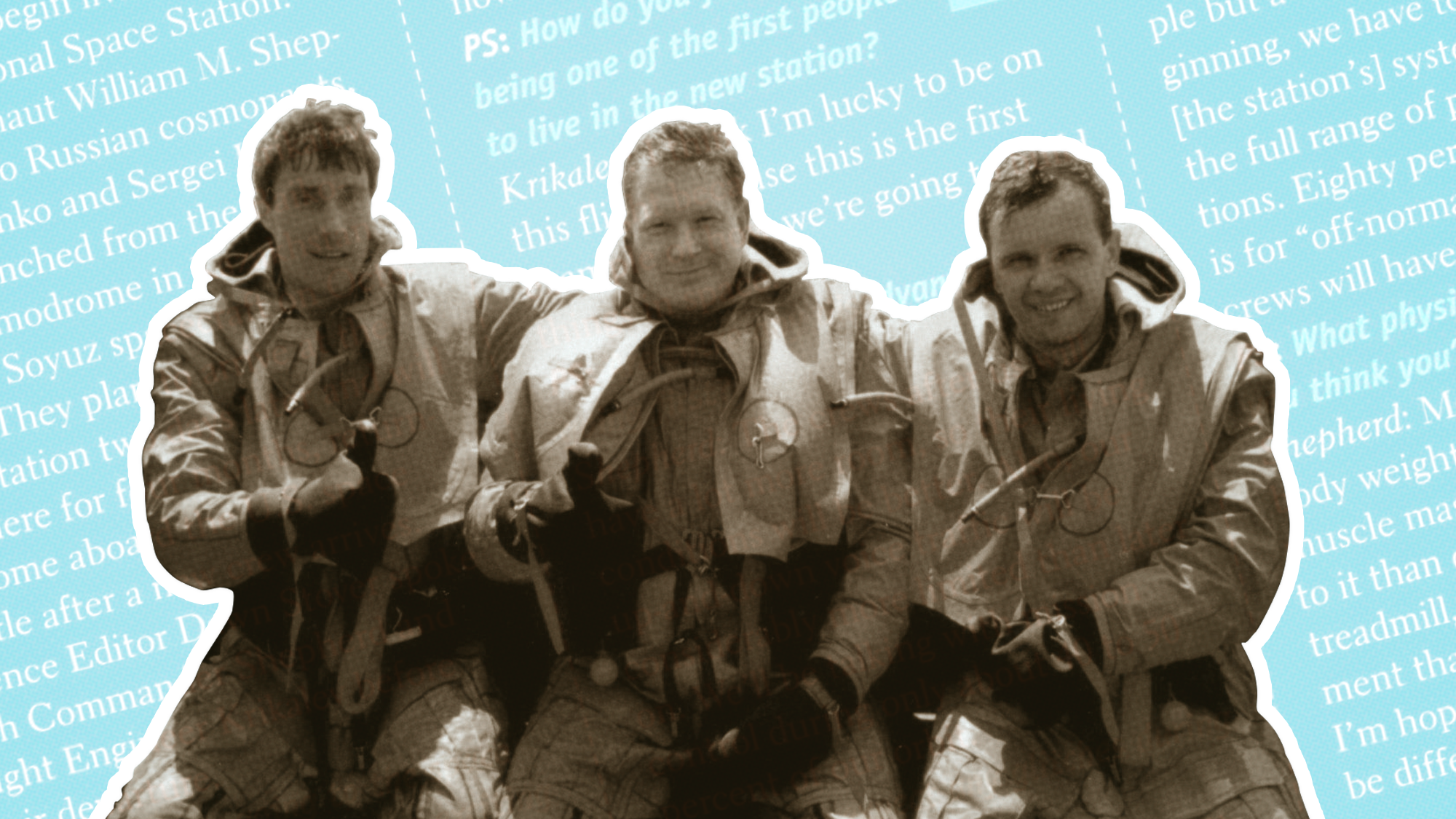

November 2000: Taking Up Residence in Space

THIS MONTH, a crew of three is scheduled to begin living aboard the International Space Station. NASA astronaut William M. Shep-herd and two Russian cosmonauts, Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev, will be launched from the Baikonaur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan aboard a Soyuz spacecraft on October 30. They plan to arrive at the space station two days later and will stay there for four months, returning home aboard the U.S. space shuttle after a new crew arrives. Science Editor Dawn Stover spoke with Commander Shepherd and Flight Engineer Krikalev before their departure.

PS: Why are you going to the space station? Wouldn’t it be more exciting to live on the moon or Mars?

Shepherd: We don’t have what we need to be able to do that. We don’t know how to do construction in space. We need a large booster, and much more energy than we can get now with solar power.

PS: How do you feel about being one of the first people to live in the new station?

Krikalev: I think I’m lucky to be on this flight because this is the first example of how we’re going to build things in space.

PS: Are there any disadvantages to going first?

Shepherd: The crews after us will have a lot more room, so their living conditions will be better. Also, our up-and-down voice traffic will be considerably more limited than later on. We’ll be talking with mission control during only about 40 to 50 percent of our orbit.

PS: Do you expect any glitches during this first mission?

Krikalev: I would expect not a couple but a couple dozen! In the beginning, we have to investigate how [the station’s] systems perform in the full range of potential situations. Eighty percent of our training is for “off-normal” situations. Later crews will have it easier.

PS: What physical changes, if any, do you think you’ll see?

Shepherd: Most people lose some body weight, and some bone and muscle mass. Some are more prone to it than others. We have a new treadmill, and other exercise equipment that hasn’t been flown before. I’m hoping that the data we get will be different from in the past.