A sealed rock fracture almost 50 feet below ground has remained home to microbes for the last 2 billion years—the oldest life ever discovered in such conditions. The nearly 1-foot sample, excavated beneath South Africa’s Bushveld Igneous Complex, predates the previous microbial record-holders by as much as 1.9 billion years. The finding could help researchers better understand the earliest stages of evolutionary life not just on Earth, but on Mars, as well.

The findings, published October 2 in the journal Microbial Ecology, come from a team at the University of Tokyo’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, who confirmed the previous oldest known lifeforms in 2020.

“We didn’t know if 2-billion-year-old rocks were habitable… so this is a very exciting discovery,” Yohey Suzuki, study lead author and an associate professor in the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Science, said in a statement on Thursday.

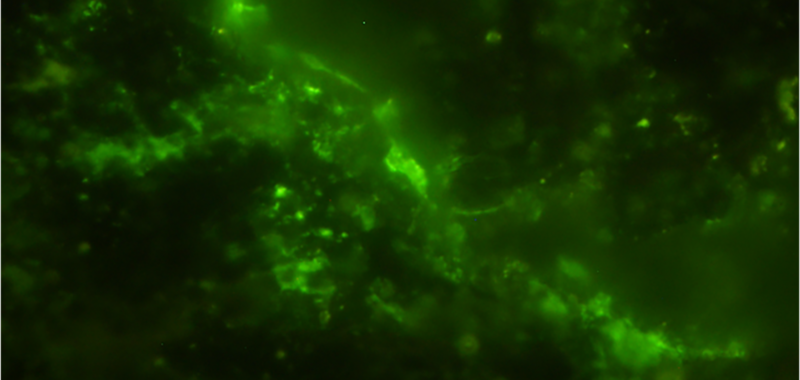

Uncovering microbes hidden from the surface world for eons required building upon the researchers’ previous methodologies for determining an organism’s age and origin. Doing so required combining three types of imaging approaches—electron microscopy, fluorescent microscopy, and infrared spectroscopy—to confirm if the microbial life really was that old, or if it came from accidental contamination during excavation and analysis. After staining the cells’ DNA, researchers looked at the microbes’ proteins as well as their surrounding clay habitat, and determined them to be both alive and native to the fissure sample.

How the microbes have been able to continue existing longer than almost any other life on Earth likely comes in large part from their habitat. Located in northeastern South Africa, the Bushveld Igneous Complex (BIC) is a roughly 41,000-square-mile region known for rich deposits of ore, including an estimated 70 percent of all mined platinum. Billions of years ago, volcanic magma cooled incrementally beneath the Earth’s surface in regions as thick as 5.6 miles.

These formations have remained largely unchanged since then, but also include tiny fissures in which microbial life became densely packed. At the same time, clay sediment capped any gaps near these cracks, trapping the tiny organisms inside while allowing nothing else to enter. Experts theorize that allowed the stability for microbial life to continue at an extremely slow pace with little-to-no evolutionary changes. With further exploration, the team hopes to detail what some of the planet’s earliest life looked like billions of years before the arrival of humans.

Future findings aren’t necessarily limited to expanding our understanding of how organisms evolved on Earth over time. The research team hopes their additional discoveries can one day also help search for evidence of life on Mars.

“NASA’s Mars rover Perseverance is currently due to bring back rocks that are a similar age to those we used in this study,” Suzuki explained. “Finding microbial life in samples from Earth… makes me excited for what we might be able to now find in samples from Mars.”