Aurich Lawson

“Gadgets aren’t fun anymore,” sighed my wife, watching me tap away on my Palm Zire 72 as she sat on the couch with her MacBook Air, an iPhone, and an Apple Watch.

And it’s true: The smartphone has all but eliminated entire classes of gadgets, from point-and-shoot cameras to MP3 players, GPS maps, and even flashlights. But arguably no style of gadget has been so thoroughly superseded as the personal digital assistant, the handheld computer that dominated the late ’90s and early 2000s. The PDA even set the template for how its smartphone successors would render it obsolete, moving from simple personal information management to encompass games, messaging, music, and photos.

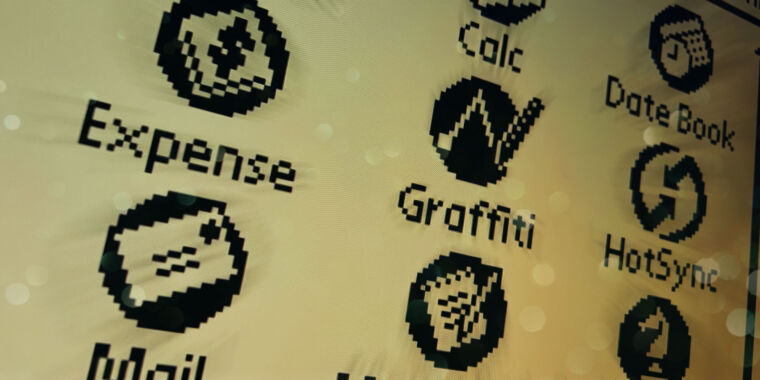

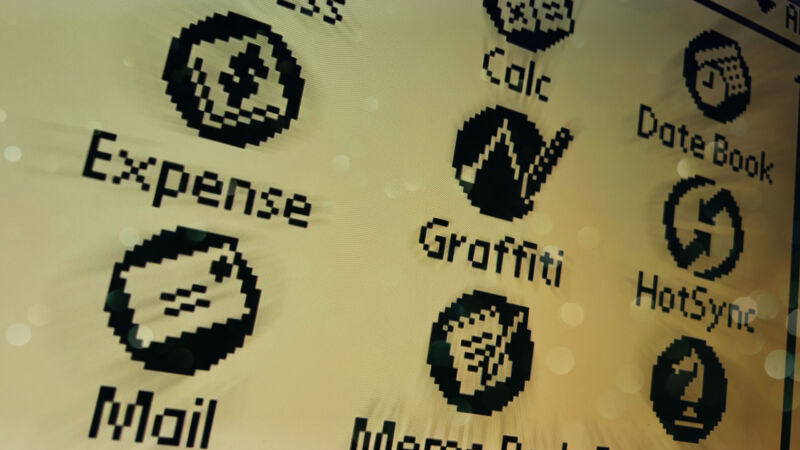

But just as smartphones would do, PDAs offered a dizzying array of operating systems and applications, and a great many of them ran Palm OS. (I bought my first Palm, an m505, new in 2001, upgrading from an HP 95LX.) Naturally, there’s no way we could enumerate every single such device in this article. So in this Ars retrospective, we’ll look back at some notable examples of the technical evolution of the Palm operating system and the devices that ran it—and how they paved the way for what we use now.

Cameron Kaiser

When Zoom(er) wasn’t meeting software

In the mid-to-late 1980s, portable computing primarily meant either heavy, luggable workstations or a unique class of pocket computers with tiny screens, small memories, and calculator-like keyboards. Jeff Hawkins, then vice president of research at portable systems builder GRiD, thought he could do better. He wanted to build a system where the screen itself becomes the input device, replacing keyboards with pens and styluses.

While handwriting recognition was an even bigger challenge for systems back then, Hawkins’ PalmPrint system simplified the task by merely matching strokes to characters instead of trying to recognize entire words. PalmPrint became GridPen, the core of the 1989 GriDPad 1900, or what we would call today the first commercially successful tablet computer. Using a resistive 10-inch black-and-white LCD as the screen and writing surface, it ran MS-DOS on a lower-power 10 MHz Intel 80C86 and weighed just about two kilograms (4.5 pounds), selling at an MSRP of $2,500 (about $6,200 in 2024 dollars).

The GriDPad line went on to be very successful for GRiD, but Hawkins increasingly considered his own creation to be too bulky and expensive. Surveying existing GriDPad corporate customers about a portable machine they would personally use, the feedback was unanimous: It had to be a lot lighter, a lot smaller, and under a cool grand.

GRiD itself wasn’t interested in producing a low-end mass-market device, but such a unit was well within the market range of Tandy Corporation, GRiD’s parent since 1988 and the owners of Radio Shack. Tandy management was entranced by the concept of what Hawkins called the “Zoomer,” so much so that the company was willing to invest $300,000 in Hawkins’ new venture to develop it, which he called Palm Computing.

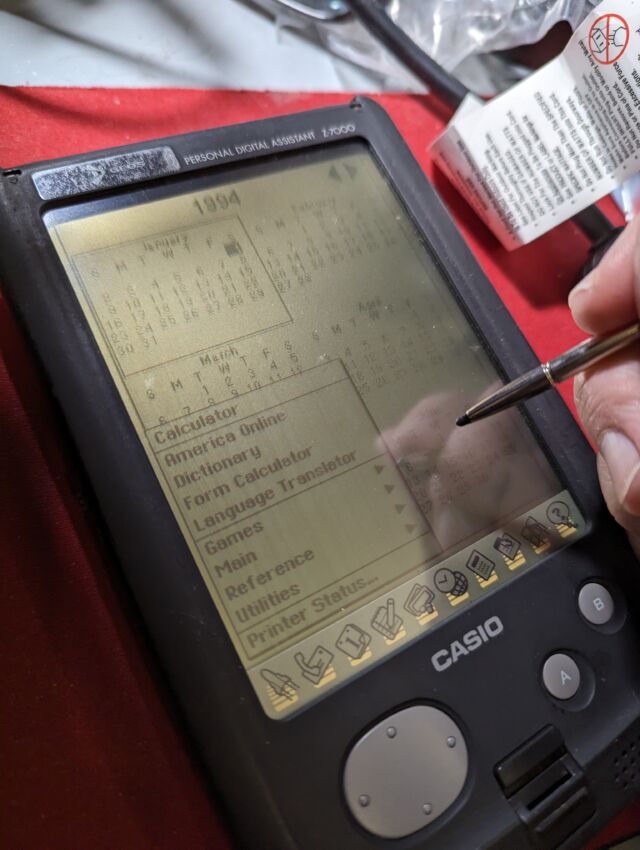

Hawkins selected GeoWorks’ PC/GEOS as the operating system based on its proven ability to run on inexpensive hardware, and Tandy brought on longtime partner Casio (also a major pocket computer manufacturer) as the new device’s OEM. To manage the growing company, Hawkins hired Apple-Claris alumnus Donna Dubinsky as CEO and later Ed Colligan as VP of marketing, fresh from Macintosh peripherals maker Radius.

Cameron Kaiser

Unfortunately, the Zoomer’s development became increasingly troubled due to corporate interference and software churn, and although underclocking its x86-compatible CPU to 7 MHz dramatically extended its battery life, it also made the unit slow and ponderous. Still, the Zoomer got to market in October 1993 at a pound in weight (less than half a kilogram) and for $599 ($1,240 in 2024), markedly undercutting Apple’s Newton MessagePad. On the other hand, it was still too large and was basically treated (and judged) as a PC, and even though its handwriting recognition was better than the Newton’s, it was still outsold four to one.