January 6, 2025

5 min read

The Real Reason People Don’t Trust in Science Has Nothing to Do with Scientists

Propaganda works, is the real upshot of a survey showing lingering post-pandemic distrust of science

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, speaks as U.S. President Donald Trump looks on in 2020.

Drew Angerer/Getty Images

“We’re all trying to find the guy who did this,” said the hot-dog–costumed protagonist of a 2019 comedy sketch, pretending not to know who had crashed a hot-dog–shaped car.

In the sketch turned popular meme, bystanders didn’t buy his story. Scientists, and the rest of us, might well follow their lead now, in contemplating November’s annual Pew Research Center survey of public confidence in science.

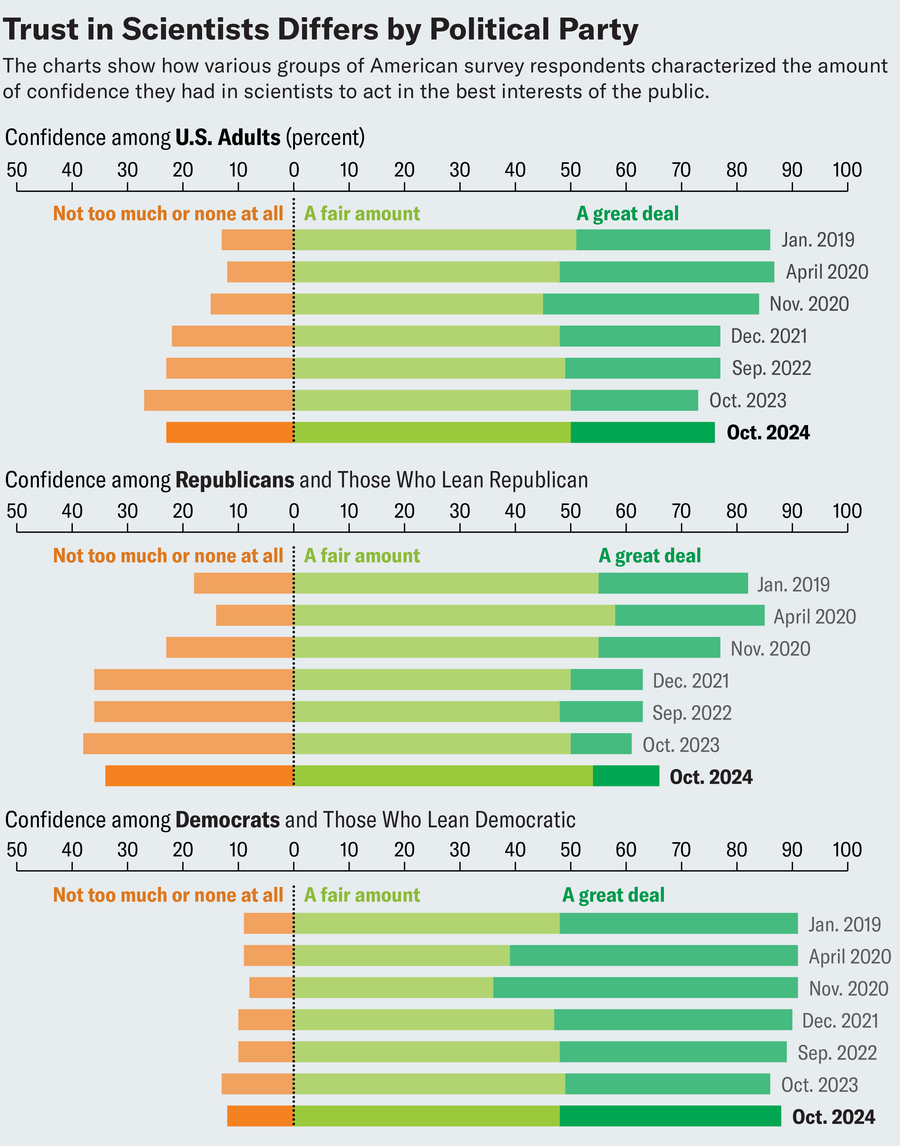

The Pew survey found 76 percent of respondents voicing “a great deal or fair amount of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests.” That’s up a bit from last year, but still down from prepandemic measures, to suggest that an additional one in 10 Americans has lost confidence in scientists since 2019.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Why? Pew’s statement and many news stories about the findings somehow missed the obvious culprit: the four years and counting of a propaganda campaign by Donald Trump’s allies to shift blame to scientists for his first administration’s disastrous, botched handling of the COVID pandemic that has so far killed at least 1.2 million Americans.

Even the hot dog guy would blanch at the transparency of the scapegoating. It was obviously undertaken to inoculate Trump from voter blame for the pandemic. The propaganda kicked off four years ago with a brazen USA TODAY screed from his administration’s economic advisor Peter Navarro (later sent to federal prison on unrelated charges). Navarro wrongly blamed then–National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases chief Anthony Fauci for the administration’s myriad pandemic response screwups. Similar inanities followed from Trump’s White House, leading to years of right-wing nonsense and surreal hearings that ended last June with Republican pandemic committee members doing everything but wearing hot dog costumes while questioning Fauci. Browbeating a scientific leader behind COVID vaccines that saved millions of lives at a combative hearing proved as mendacious as it was shameful.

The Pew survey’s results, however, show this propaganda worked on some Republican voters. The drop in public confidence in science the survey reports is almost entirely contained to that circle, plunging from 85 percent approval among Republican voters in April of 2020 to 66 percent now. It hardly budged for those not treated to nightly doses of revisionist history in an echo chamber—where outlets pretended that masking, school and business restrictions, and vaccines, weren’t necessities in staving off a deadly new disease. Small wonder that Republican voters’ excess death rates were 1.5 times those among Democrats after COVID vaccines appeared.

Amanda Montañez; Source: Pew Research Center

Instead of noting the role of this propaganda in their numbers, Pew’s statement about the survey pointed only to perceptions that scientists aren’t “good communicators,” held by 52 percent of respondents, and the 47 percent who said, “research scientists feel superior to others” in the survey.

That explanation echoes the “kick me” sign that scientific institutions have taped to their backsides over distrust at least since 1985, when the U.K.’s Royal Society warned of “[h]ostility, even indifference, to science and technology,” in a report, The Public Understanding of Science. “Scientists must learn to communicate better with all segments of the public,” it concluded.

That prescription matches scientific responses to the Pew Survey results, with National Academies of Sciences chief Marcia McNutt telling the Washington Post: “[T]his gives us an opportunity to reexamine what we need to do to restore trust in science.” And it matches the advice in a December NASEM report on scientific misinformation: “Scientists, medical professionals, and health professionals who choose to take on high profile roles as public communicators of science should understand how their communications may be misinterpreted in the absence of context or in the wrong context.” This completely ignores the deliberate misinterpretation of science to advance political aims, the chief kind of science misinformation dominating the modern public sphere.

It isn’t a secret what is going on: Oil industry–funded lawmakers and other mouthpieces have similarly vilified climate scientists for decades to stave off paying the price for global warming. A study published in 2016 in the American Sociological Review concluded that the U.S. public’s slow erosion of trust in science from 1974 to 2010 was almost entirely among conservatives. Such conservatives had adopted “limited government” politics, which clashes with science’s “fifth branch” advisory role in setting regulations—seen most clearly in the FDA resisting Trump’s calls for wholesale approval of dangerous drugs to treat COVID. That flavor of politics made distrust for scientists the collateral damage of the half-century-long attack on regulation. The utter inadequacy of an unscientific, limited-government response to the 2020 pandemic only primed this resentment—fanned by hate aimed at Fauci—to deliver the dent in trust for science we see today.

“Surveys are well-suited for measuring attitudes and describing changes in views over time. They are less well-suited for parsing potential causal factors,” says survey lead author Alec Tyson, when asked why Pew refrained from making this obvious connection. “While beyond the scope of this particular effort, we share an interest in scholarly efforts to understand the role of partisan rhetoric and the broader information environment in shaping views.”

Their aversion doesn’t mean we all must play make-believe about where the distrust for science springs—from politics. Perhaps the clearest sign of the propaganda campaign is that Republican politicians have gotten high on their own supply of antiscience hokum. With Trump headed back to the White House, his profoundly unqualified pick for Department of Health and Human Services chief is Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., whose antivaccine advocacy contributed to 83 measles deaths in American Samoa in 2018. For the National Institutes of Health he has picked Stanford University’s Jay Bhattacharya, one of three authors of a lethally misguided 2020 plan—pushed then on the Trump White House—to spur coronavirus infections that would have caused, “the severe illness and preventable deaths of hundreds of thousands of people,” according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Neither of these hot-dog-guy picks should be allowed anywhere near our vital health agencies.

“It’s obviously this guy, right,” say the cops at the end of the hot-dog-guy sketch, before setting off in his pursuit. Making that same call on recognizing where the distrust for science comes from today is just as simple.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.