This story contains major spoilers for Sinners, including discussion of the ending.

Ryan Cooglerâs fourth film, Sinners, was a sensation this opening weekendâit pulled in $45.6 million domestic and over $60 million globally, and perhaps as importantly, became the center of the cultural conversation despite landing at the same time as the first round of the NBA playoffs. Itâs become a bonafide phenomenon, causing uproar over where and how it could be seen in its âproperâ 70mm IMAX format, putting the city in a chokehold and prompting sold out screenings from Thursday afternoon through Sunday night.

The film itself is a fascinating curio weâll be arguing about for yearsâa horny, funny, violent, frightening and thrilling Carpenteresque carnival attraction with a Williams-worthy knockout Ludwig Göransson score that is practically a co-lead in the film, Spielberg-quality blocking and pacing (and elite Spielberg oners), and a fun, cheap infusion of eye-in-the-door-hole melodramatic â80s-sleepover Rick Baker-y trash, all of which combines to make a flick with swaggering, summer-blockbuster mojo that came a few months too soon.

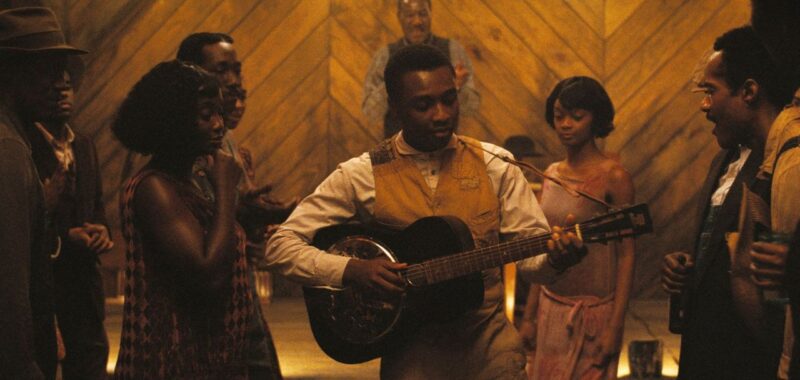

Warner Bros./Everett Collection

The very few audience members who havenât enjoyed it (I wonât lend any one stupid score-aggregating site the credit it does not deserve, but the film is âperformingâ very well) seem to be bumping on the lack of imagination the film brings to the conventions utilized to tell its story. Itâs no longer a secret that Sinners is (to a degree) a vampire film, and one that uses antiquated fairytale-hokey vampire lore to make the rules of its worldâwooden stakes through the heart, pickled garlic brine that sizzles like holy water or hydrofluoric acid. But focusing on the vampire of it all, and even the blues, is largely missing the point. The film is a very thinly-veiled parable about how the vampiric mainstream love and acceptance of white institutions compromises Black artistry.

Lazy critics have been putting Ryan Coogler in conversation with Spike Lee for as long as heâs been a filmmaker, for obvious and extremely dumb reasons. Coogler has always been a disciplined, structured storyteller, a culture-literate pop politician naturally able to navigate the studio system in the era of IP in a way Spike could never dream of. But in this case, Sinners is in conversation with Spike not just because itâs the work of a young Black filmmaker with electric chops, an encyclopedic handle on the history of cinema and impeccable instincts, but because this specific film is one of the most purely symbolic, metaphorical recent movies/bully pulpits you will find outside of Spike’s unique, voicey cinematic universe.

To say a lot of Sinnersâs plot dressing is beside the point wouldnât be right, but also wouldnât be wrong. Either way, letâs quickly run it downâand hereâs your final spoiler alert, youâre on your own after the end of this sentence. The core relationship in the film is between the Moore brothers, Elias (Stack) and Elijah (Smoke), twins who survived the German trenches and two separate European-diaspora organized-crime families in Chicago. Theyâre both played by the great Michael B. They hail from Rick Rossâ ancestral home of the blues, Clarksdale, Mississippi, portrayed in the film as a cotton town in apparent need of another juke joint. Having realized the Northern metropolis is just another racist Southern town with tall buildings standing in for plantations, the native sons have come home from Chicago to provide for their community, because Mississippi is the devil they know, and because theyâre hustlers, distributors looking to bring authentic experience to their brethren.